NatHack 2025 - Cranking 90 Hour Work Shifts in the Hackathon of All Time

Nov 16, 2025

5 minute read

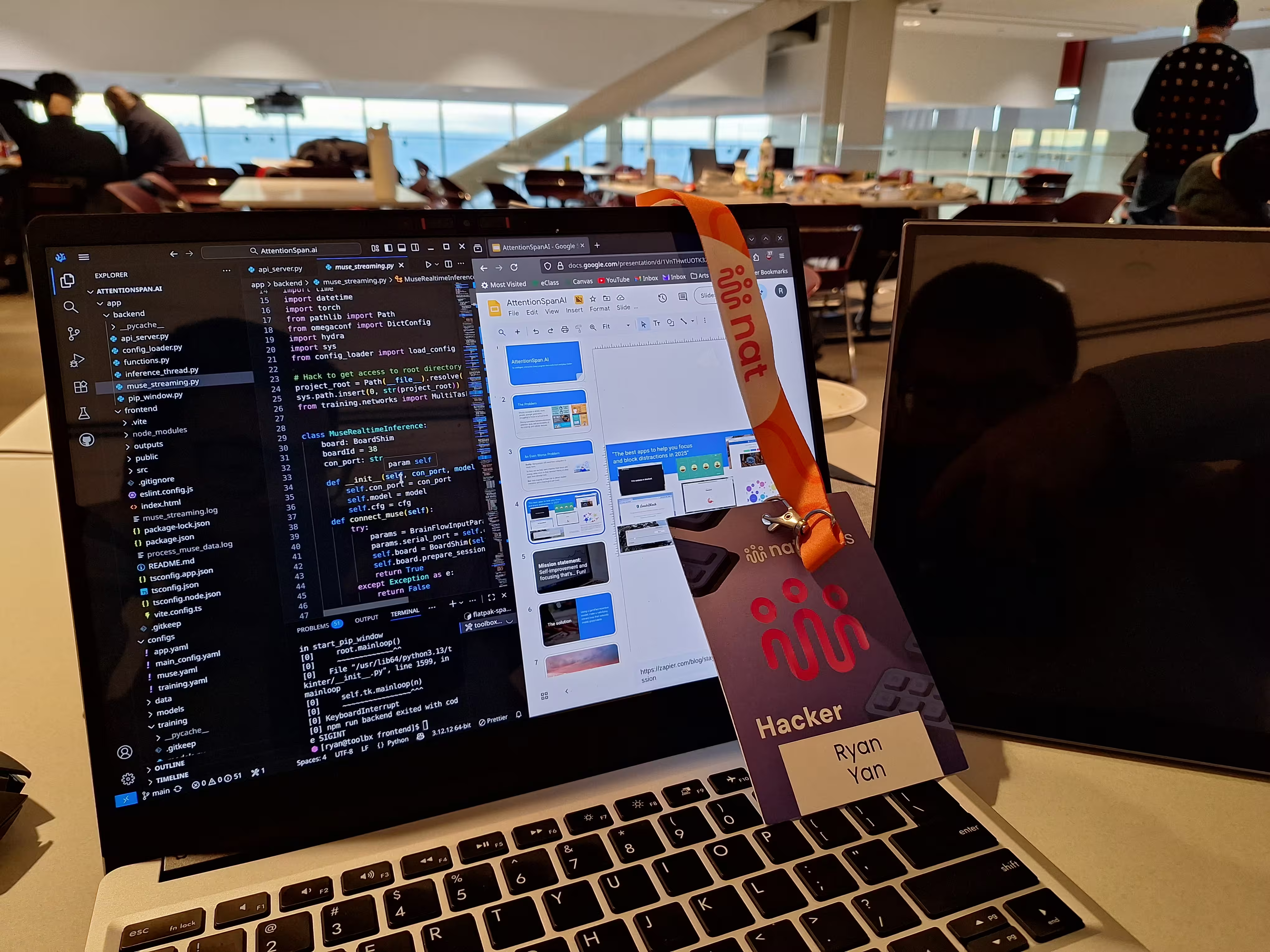

NatHack 2025 at the University of Alberta is an annual hackathon focused on hardware-oriented projects in Neuroscience, Medicine, Education, and the environment. This year, I got to compete over 4 full days of prototyping, developing, and pitching Focus Tree, by our team of 5, AttentionSpan.Ai.

This page covers my personal experience and the lessons I've learned during this hackathon. See my project page for the technical aspects of our submission.

Coding vs "Entrepreneuring"

- Brainstorming concepts and ideas

- Market and technical research

- Planning out hardware, programming tools, and project structure

- Task assignments and daily sprints

- Writeups and documentation

- Marketing pitch (to judges acting like investors) just like any startup company would. Outside my primary programming role of machine learning and data collection, I learned how to pitch and market our product to panels of "clients", supported by market research and statistics. Beyond the slide deck and script, I also came to understand the importance of researching our clients' expertise, generating expectations, and anticipating questions so nothing is confused. A massive thanks to all the advisors, sharing their secrets on how simple it is to appreciate how "less is more" when presenting yourself.

NatHack is pretty unique in how it focuses on entrepreneurship and long-lasting products vs quick technical showpieces. They place strong emphasis on inviting a wide range of unique industry experts, so it isn't biased towards programmers. Plus, all the prize money can only be spent on funding future development, so winners are incentivized to continue to further develop their projects. It's an interesting format I appreciated, despite not winning a top 3 spot myself. In fact, I think other hackathons, especially game jams, could take inspiration to support small projects developing towards the final release.

Honestly, all this wouldn't even be worth mentioning if everyone in school got to learn or experience the idea -> market pipeline. In contrast, I doubt the vast majority will ever get this opportunity unless they actively seek out events outside their curriculum. Whatever mix of inaction, indifference, or laziness results in the majority missing out on truly interesting and educational events like this is still a missed opportunity and a mighty shame. Plus, I actually enjoyed myself and felt much more fulfilled in a 40-hour hackathon than forced to develop shitter projects for classes.

Working With Hardware

Another oddity I'd never noticed was the lack of hardware-focused hackathons. Outside obvious limitations of online-only events and industry-specific circumstances, there is a dominance of software and a lack of hardware-oriented projects in the developer ecosystem. Not too surprising, given how accessible a personal laptop is to buy, and how extension-free and open-source software has become. However, there is so much potential that's lost with the "apps on common devices (smartphones, PCs)" mindset, untapped in the current industry.

As examples of this, many of the projects at NatHacks used sensors and micro-controllers to interface directly with users -- things that couldn't be done with just software alone. Body sensors to detect health conditions, controller mechanical limbs with the mind, heck, our project was an interactive focus application, scanning brainwave data from a Muse 2 headset.

And in terms of mindset shift, it ain't so different from the already familiar mouse and keyboard. People are already so accustomed to these two objects that we programmers hardly need to consider how different users may interface with them. Once more exotic components are introduced, then we need to consider:

- How we expect users to use the hardware

- How to extract and use the data from the hardware

A great example is video games, where the primary controller scheme is keyboard and mouse, or a controller. With how standard player controls are within established genres, games can assume common patterns like WASD -> move, right click -> aim in FPS games, ESC key -> menu, etc. All the more reason I praise exceptionally creative games using novelty hardware to create a completely unique experience. Some notable examples include:

- Before Your Eyes and Goodnight Universe - Both narrative driven experiences by the same creator. You use a webcam to track blinking and eye movements, which integrates beautifully with the story and gameplay.

- Just Dance (pre-2023) - Using the Xbox Kinect camera to dance along was so much of my childhood, even if Microsoft basically killed support after 2022. An infinitely novel idea, very complex technology, with so much potential if only more games made use of it.

- Astro Bot - To also rep Playstation. Astro made use of all the features on the Dualsense, including the touchscreen, microphone/speaker, and gyroscope, to turn a standard action platformer into a uniquely interactive and refreshing entry in the genre. These successes can and should be extended to other industries, in my opinion. If not for the gap in market potential, but just because we need more fun stuff to play around with in our lives.

Enjoying Networking

Maybe a confusing oxymoron or not, I never enjoyed networking events that felt like blitzing through surface-level discussions and LinkedIn farming. It's not that people can't start nuanced and in-depth discussions themselves; rather, most "networking sessions" fail to facilitate an environment to encourage networking. In other words, bad events haphazardly throw networking on top of their schedule and solely rely on people to figure out how to start conversations.

The persistent four days of NatHack and other longer hackathons/events make connections much easier when like-minded people stay in the same building for extended periods. They also hosted many extra events, like trivia and game sessions, naturally connecting people based on mutual interest and hobbies outside of work. The most effective measure, however, was how that NatHack didn't advertise itself as a networking event, yet facilitated easy networking through the event's structure. Actively engaging participants with friendly advisors, experts, and volunteers nurtures a cooperative environment where everyone is working in unison.

During NatHack, I held lengthy conversations with other people about how to pitch our project, volunteered to be interviewed about C.S. job opportunities, and debated project ideas and future plans with other teams. Chatter started and felt leagues more natural and genuine than in conventional networking events. Connections happen very casually, and everyone and everything felt more meaningful. Guess that is the nature of smaller, tight-knit events.

Catering actual food also helped with morale. I was fully expecting 12 rounds of pizza, so I'm sure everyone appreciated the effort. Forgot to take pictures of lunch and desserts, so here was some of my dinner.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed this hackathon. With so much enthusiasm, my body pushed through the 10-hour shifts we went through every day, and now I wanna gather another team for a second round. Signing up for events like these is a really refreshing way to test my skills and find motivation to develop meaningful projects. I believe that anyone who has the time and is looking for a bit of competition to drive programming should consider competing in similar time-limited development challenges, if not just to push oneself, also as an excuse to be surrounded by other cool people.

Even without making the top three, my team and I had a great time! Definitely recommend NatHack (non-programmers are actually encouraged) in the future.