Custom Game Engines

2025

15 minute read

While pursuing the certificate in computer game development at the UofA, I participated in a game engine class (CMPUT 350). We focused on rigorous memory and performance optimization in c++, engine architecture, graphics rendering, and common game features like camera movements and physics collisions. Both games below represent the two capstone projects, each implementing two different architectures and many features we implemented into video games. The only external dependency was SFML - a multimedia library, to simplify cross-platform graphics rendering, input, and audio.

Bolo - Object-Oriented Programming

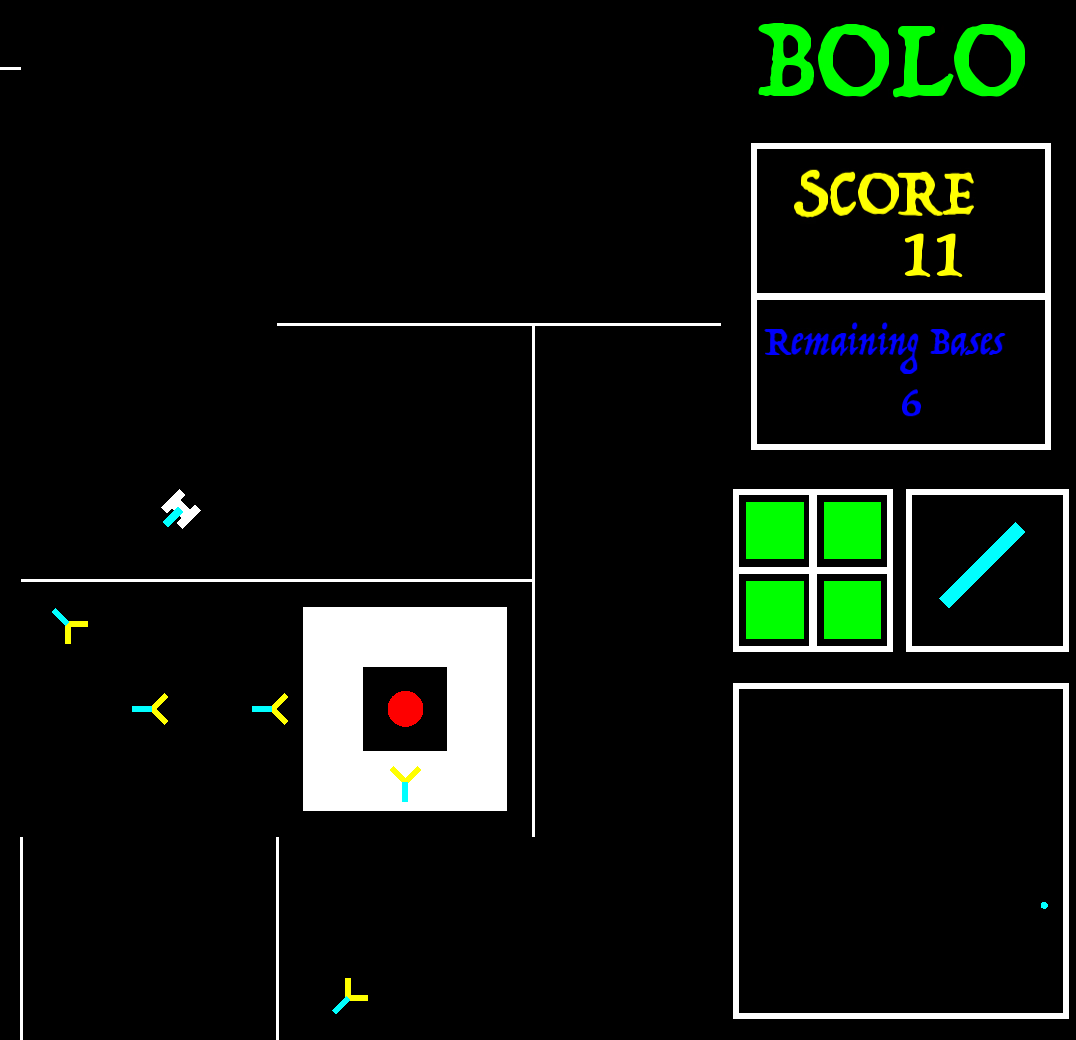

Bolo is a top-down tank shooter based on the original 1982 Apple II game (not to be confused with the other 1987 Bolo by Stuart Cheshire). The player navigates around procedurally generated levels, attempting to hunt and destroy the enemies guarding the 6 bases on the map. Progress through harder and harder levels, and rack up high scores as you go.

Engine Structure

Making an object-oriented engine is conceptually simple when you break down what needs to happen on every frame. Generally, a standard engine loop looks like this:

- Remove any objects that are no longer alive.

- Add any objects that have been created in the last frame.

- Process any key hits/inputs

- Update all game objects

- Process collisions

- Do late updates on all game objects

- Render the background

- Render the foreground

Depending on how you render graphics and manage memory, some steps can be broken into multiple subparts. SFML for

example, defines a RenderWindow object which we "draw" into SFML shapes (lines, circles, rectangles), then we call

window.draw() at the end of each frame to render. A loop filters out background/foreground objects and draws them in

order onto the window. window.clear() also needs to be called so the previous frame doesn't persist over. These all

need to be done during the rendering steps, and can become their own intermediate steps within the engine loop above.

From the perspective of an engine developer, only a "context window" is provided so the game programmers can interface with the engine without directly modifying it. Because the engine is meant to be portable across different projects, this abstraction both abstracts and simplifies engine commands to well-documented functions within each view. A portion of our game context looked like:

class GameContext

{

EngineView *EngineContext;

DrawContext *ScreenContext;

DrawContext *GUIContext;

// Other context as needed...

};

Where EngineView provides functions to add and get objects in the engine, and DrawContext simplifies drawing logic,

screen resizing, and segmenting portions of the screen for different UIs. Bolo defined the right-hand side as the GUI

window, containing its own coordinate system and conversion logic.

Game Objects

All user-made objects inherit from a base GameObject class, providing all virtual functions that the engine runs on

every frame. Notably, this means that each object is responsible for defining all of its behaviors, independent of all

other objects.

class GameObject

{

virtual void Update(GameContext *context);

virtual void RenderForeground(GameContext *context);

virtual bool IsAlive();

// Other logic like handling input, render background...

};

We also define collision objects, which add a bounding box and a CollisionEnter function to implement collision logic.

The engine checks collisions between all dynamic and static objects (static-static checks are skipped, they never move),

only calling CollisionEnter if a hit is found. Beyond a simple bounding box, objects like the player, bullets, and

enemies are defined by their individual shapes.

class CollisionObject : public GameObject

{

virtual bool IsStatic() const = 0;

virtual void CollisionEnter(const std::shared_ptr<CollisionObject> &obj) = 0;

virtual const Rect &GetBounds() = 0;

virtual const std::vector<Shape> &GetShapes() = 0; // Shape is one of circle | rectangle | line

};

This method is easy to comprehend, and by far the most common architecture in commercial game engines. However, it becomes very cumbersome when trying to reference other objects, and requires additional systems to make Bolo work. Notifications, weak pointer references, or extra virtual functions for the engine to run.

Shapes and Collisions

Our engine supported circles, axis-aligned bounding boxes (rectangles parallel to the axis), and lines. This needed 6 functions to handle the combinations of 3 potential shape on shape collision. The basic formulas are very common, and some can determine the exact point of collision when feasible. Two lines crossing will always produce one point of collision. Other shapes can produce multiple points, in which we chose to return the "closest" point to the shape's origin. Some helpful sources were Mozilla's article on 2D object collisions and Learnopengl collisions between circles and AABB boxes.

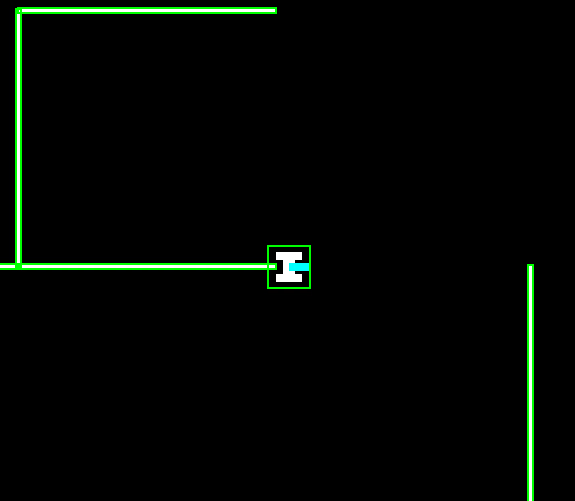

We still kept the bounding box as a fast AABB check to determine if two objects are potentially colliding before checking every shape of the object. Particularly, this gave us more precise collisions than a clunky square. Here you can park the tank into the wall, which overlaps the bounding box but not the actual tank itself.

Memory Management

The engine stores multiple vectors of shared pointers of game objects, a master vector of all objects, and two collision vectors for static and dynamic objects. This saves needing to loop through every object on every frame during collision checks.

All game objects will be a different size in memory (depending on how much code the user implements). We rely on this dynamic heap allocation and pass pointers around between systems. Of course, dynamic memory allocation and scattered access are very slow, but hard to avoid in an object-oriented program since objects can't guarantee their own size and cannot be aligned in consecutive memory. This suboptimal memory access is what we address in the second engine/game with ECS, a completely different approach to object storage and access.

// 3 vectors, filtering objects if they are collisions and/or static

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<GameObject>> mObjects;

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<CollisionObject>> mDynamicColObjects;

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<CollisionObject>> mStaticColObjects;

Because of this system, the most annoying part of developing Bolo was managing references between and within objects. As an example, when a bullet hits an enemy, we needed to know whether the bullet was shot by the player, not an enemy, before incrementing the score. Even worse, when a player shoots and spawns a bullet, we need a pass in a reference to the player itself to prevent collisions against the player's own bullets. Since the engine stores shared pointers of game objects, searching through this vector every frame would cost expensive dynamic casts. Hence, the best solution ended up devolving into chains of weak pointers to shared pointers of objects, a convoluted debugging mess.

Game elements

The game itself is defined in a separate folder from the engine. Bolo.h is defined as the master object, initializing

the first game objects and controlling the game loop by maintaining the state of the game. The basic game loop goes as

follows:

- Show home screen. Prompt the user to input the maze density

- Generate the maze and bases

- Gameplay (Player moves and shoots the tank)

- If the player dies, show the game-over screen and reset to the home screen

- If all bases are destroyed, show the congrats screen and generate a new level PLAYER_PROMPT -> INIT_LEVEL -> GAME_PLAY -> (END_LEVEL -> INIT_LEVEL OR GAME_OVER -> PLAYER_PROMPT)

Maze Generation

From a full 50x50 grid of walls, our maze generator does a depth-first search across the whole maze, deleting walls as it traverses, until a valid maze is produced. Walls are then culled to the desired density, and bases are added where there's enough space to spawn enemies. There are many clever ways to represent this grid of walls, and I choose this conceptually easy-to-understand matrix of cells defined as:

struct Cell{

bool visited;

bool wUp;

bool wDown;

bool wLeft;

bool wRight;

};

For what we wanted to achieve, this is a very simple and quick method for maze generation.

Enemies

The enemies themselves just move and shoot semi-randomly. What took the most thought was the enemies and how to stop them from getting stuck and endlessly spinning. We initially had it so that the enemy transitioned states once it had traveled a distance equal to the base radius. This did not work since a rotation would throw it off, and the enemy would start spinning at the edge of the base. The solution was to check the intersection between the bounding box of the enemy and the base, and transition states once the result was empty.

There was a very annoying bug that happened when an enemy outside the base would move beside the walls of the base when the base had low health. Then, the base would regenerate health, and the walls would expand on top of the enemy, making the enemy get stuck. Our solution was to make the enemy undo its last action when its bounding box intersected with the walls of the base if it was at its largest size. This made it so that the enemies never wandered into the base to begin with, even if it was smaller. Another bug was that enemies inside the base would hit an enemy outside the base before it left the base, leading to the inner enemy rotating back into the base. This left a minimal chance for the enemy inside the base to rotate back into the center of the base. When the base spawned another enemy, they would both get stuck. The fix was to immediately kill an enemy if it spawned and collided with another enemy on the first frame.

UI

Important information about the game state is updated in the main Bolo object and displayed on the right-hand side of the screen. Score, remaining number of bases, direction to the nearest base, the tank's orientation, and a minimap of the player. Since we're only using lines and rectangles, it took a lot of trial and error to get it to look right, but it ended up looking pretty nice.

SKKS - Entity-Component-Systems

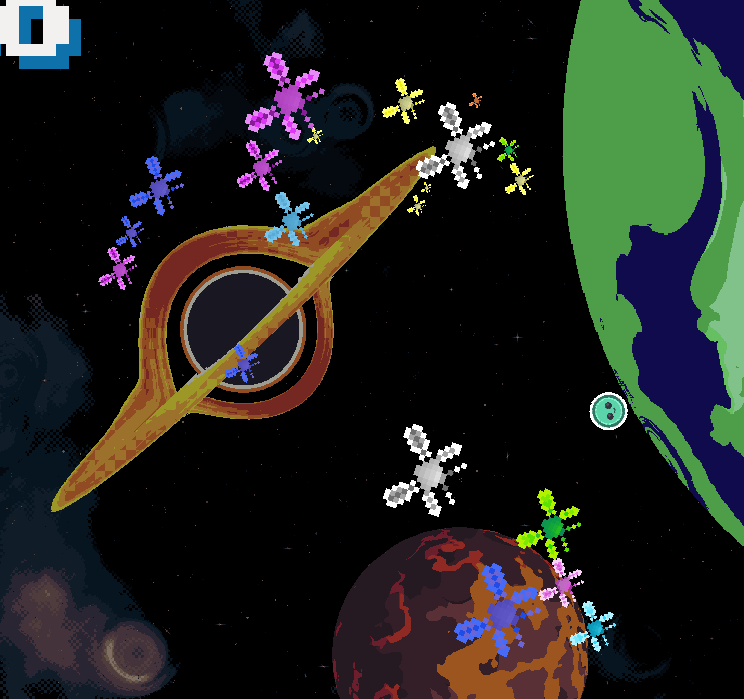

SKKS is a physics-based platformer where you fly across planets by building speed and momentum to launch yourself to victory! Navigate around unique levels, collect stars for high scores, and get absorbed into the satisfying movement of space-based physics.

Engine Structure

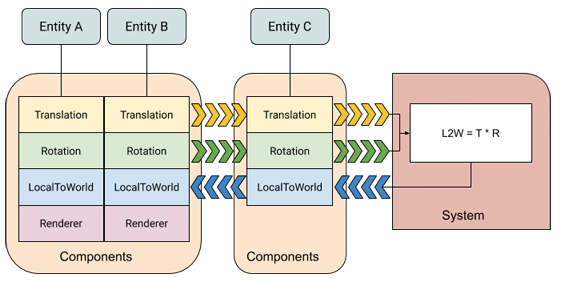

The biggest difference between OOP and ECS (Entity-Component-Systems) is how game objects are stored and accessed.

Instead of individual objects containing all their data and logic, we break down bundles of raw data (ex. ints, strings,

bools) into reusable Components, and game logic (e.g., moving, drawing, collision) into Systems. With our

well-defined components of set size, we can store our data into a matrix-like, fixed-size array of vectors of components

directly on the stack -- giving us localized, concurrent memory access. For example, consider multiple enemies in the

world with a LocationComponent and MovementComponent. Within our component storage, all the LocationComponents

will be stored together in one vector of the matrix, and MovementComponents in another.

Game objects are now defined as Entities, composed of different components within the component storage by id.

Systems then check all entities if they have a certain subset of components and perform some update to the component

(raw data). For example, a MoveSystem might look for entities with a LocationComponent and MovementComponent, and

if so, update their location given the value in movement.

Diagram taken from https://docs.unity3d.com/Packages/com.unity.entities@0.1/manual/ecs_core.html

For game development, this requires a big mentality shift. Whereas virtually all game engines and games revolve around OOP, writing generalized components and systems for potentially many entities, is the opposite of programming everything inside an object. Think of composition vs inheritance. Where, instead of inheriting all the properties of a parent object, you define an entity with multiple smaller, reusable components. Composition in traditional game dev is usually a good middle ground between pure OOP and ECS, where components can contain both data and logic as one class. However, this is a pure ECS engine, so all data and logic are separated.

Managers

Within the engine are some necessary managers for storing and accessing essential data. These are called by systems, or directly within the engine during initial loading of raw assets:

- Component Storage: Manages adding, storing, and removing one type of component by id. We also maintain extra data , such as an entity to components mapping for fast cross-checking.

- Entity Manager: Tracks all entities and provides functionality to query and retrieve an entity's component(s). Also stores all our component storages, one for each type.

- Sprite Manager: Registers images (PNGs, JPEGs), crops, pad, and places them into an atlas texture.

- Sound Manager: Registers and plays sounds from music files and sets their attributes. Manages a buffer for playing sounds.

- Shader Manager: Registers shader files (.vert/.frag) for future rendering.

Component Storage and Entity Manager uses c++ template meta programming, giving compile-time execution for querying and adding components by type. Templates also allow us to handle any arbitrary components, and give us really convenient functionality like querying for all entities with certain components:

entityMgr.template ForEachEntityWith<LocationComponent, MovementComponent>(

[&](ECSEngine::EntityID id, LocationComponent& location, MovementComponent& movement)

{

// system logic here

});

An atlas texture where multiple sprites are merged into one massive texture. This way, we can keep every sprite loaded

into the GPU all at once. The register step in the sprite manager had to crop a sprite sheet into an image, pad it, then

draw it onto the atlas texture, which SFML was terrifyingly slow at. My optimization ended up being to copy the raw

pixel data as a vector, caching it, then performing a direct raw memcpy to draw into the atlas.

Scenes

Another deviation from OOP engine design is how we define scenes/game states. Our game is composed of multiple scenes, where each scene is its own enclosed engine with managers, components, and systems. Scenes this way can register only what they need, and exist as an abstract state of the game. The real engine maintains a stack of these scenes and runs the systems of the top scene every frame. Push and pop commands are what change the game state.

To further optimize creating scenes, each scene is defined as a function with an inner scene build function, which is passed into the engine. When a scene is pushed onto the stack, only the build function is executed. This lets us separate the initial registering of assets and components from the rebuilding of the scene (basically resetting the scene to its original state).

Maps

We import and define everything, levels, UIs, and even asserts, in the game using .txt files. In fact, you can play

around with the level files right now in the itch.io build. Each scene uses our Maploader, a giant text parser that

reads our text files and creates/registers entities with their necessary components into the scene. A snippet of the

first level looks like:

// Player

// spritesheet tex-X tex-Y tex-W tex-H radius pos-X pos-Y mass animations

PLAYER player.png 0 0 64 64 20 0 0 1 explosion

// Planets

// spritesheet tex-X tex-Y tex-W tex-H radius pos-X pos-Y mass collision animations

PLANET planets/moon.png 0 0 1000 1000 300 700 1300 800 1

// Stars

// spritesheet tex-X tex-Y tex-W tex-H radius pos-X pos-Y animation

STAR animations/Star.png 0 0 32 32 15 133.3 22.55 star

Game elements

The game files are separate from the engines, like with Bolo, but are composed of many component and system files instead of object files. We also have sprites, shaders, and audio, as opposed to the basic vector art from before. Sprites allowed SKKS to look and interact much nicer, feeling much more like a modern game. The game loop is also pretty simple:

- Show home screen. User clicks on the level.

- Show transition slide in. Build the level.

- Gameplay (Player moves around level)

- If the player dies, reset the level (transition back to itself)

- If player makes it to the portal, transitions to the next level.

Physics

The main gameplay of SKKS revolves around the physics of mass and gravity to soar around planets at fast speeds. We achieve this with a gravity system that takes in the mass component of all entities, and applies the calculated force onto their velocity component. All collision objects are circles in our game, making circle-to-circle collision and finding the normal where they contact very simple.

ECS makes this dead simple and scalable, since we only need to add a mass component to every physics object, and our one system will take care of updating any movable objects. Our levels are built around this feature in mind, incorporating unique challenges and navigation puzzles.

Camera System

The camera will look ahead of the player when they move, and will smoothly hover within a certain dead zone of the

screen. Assigning the player the CameraComponent, the camera system fetches the player's current location and

velocity, and determines how to move the camera, given its previous position and distance to the dead zone. Multiplying

this by a decaying smoothing factor makes the camera nice and fluid, which works perfectly for a game where the player

can stay still and fly around space sporadically.

Sprite/Animation/Shader Rendering

Every scene has a sprite rendering system, which grabs every sprite and location component. Each sprite component has its sprite ID within the sprite manager, alongside other metadata like draw layer and size. We request the sprite manager to fetch the corresponding atlas texture's coordinate and build a vertex array of triangles. This lets us draw everything in one go, saving massive overhead.

Animations are even simpler; swap the sprite components' id every x frames from some animation reel of sprites. The bugs and the flag (last level) both have a flapping animation. Similarly, for shaders, we maintain separate vertex arrays and draw them separately with the shader attached. See the portal effect when you move over it, and the heat effect from the lava planets.

Enemies

The bug enemies are much more advanced than in Bolo, hunting the player in packs using Boid's flocking algorithm. Note how they cluster up as they fly towards the player.

Final Comparison Between OOP and ECS

There is a seemingly infinite amount of information that exists about theorems, laws, and "best" practices for coding. Liskov substitution principle, decoupling, inheritance vs composition, documenting in comments vs in code, or even culture wars about the single best and worst programming language across every discipline of computer science. In reality and from my experience, these choices mainly depend on the objective at hand -- not just personal preference. Both architectures, OOP and ECS, have powerful benefits and annoying downsides to develop a game engine with, despite achieving the same goal of making a video game.

OOP is by far the most common design pattern, used in basically every commercial game engine and the introduction to

software engineering. It's easy to comprehend, even for non-programmers, and so is basically the de facto method

everyone will learn. This is especially important from a game designer's perspective, thinking of every element in a

game as its own object has real-world similarities, making development in studios with multiple non-programmer

specializations easier to understand. Having exact control over each individual object can also be a good thing, as it

makes internal scripting and debugging compacted in one file. In practice, however, when projects begin to scale, having

to consider the interactions between many hundreds or even thousands of objects, features, and systems, and implementing

them all in each object's code becomes excessively lengthy and overwhelming to remember. The usual solution of

inheritance as abstraction often becomes very limiting, as trying to draw boundaries between sub-objects ends up causing

more boilerplate to manage. For example, players, NPCs, and enemies inheriting from an Entity class might work

initially, but would it make sense to extend a static tree class off Entity? What if the players and NPCs now have

inventories, either Entity implements the inventory data, but enemies don't need it, or each player and NPCs implement

their own inventory, doubling the amount of code with just one feature. Splitting Entity into smaller classes like

StaticEntity and InteractEntity might work initially, but as development continues, requirements change, which

inevitably means changing every single object down the inheritance tree. OOP is easy to comprehend and work on, which is

essential for multi-disciplined projects, but very rigid in structure and hard to scale with new features.

- Full control over every object

- Common methodology, easy to comprehend

- Inheritance can become restrictive really fast

- Need to consider interactions between every object, excessive code

ECS was designed to ensure fast, concurrent memory access for its data, whereas OOP objects are isolated in suboptimal memory chunks. Using systems to access/modify concurrent data in theory provides a substantial boost to memory performance. Defining "objects" instead of entities associated with components, operated on by systems, makes scaling as easy as defining what entity has what component. Composition instead of inheritance: giving any moving entity a move component, any inventory entity an inventory component, collisions a collision component, and so forth. New components and systems are, by design, scalable across every entity in the game, making future planning surprisingly easy to consider. While I have come to prefer ECS over OOP, thinking of objects this way is much less intuitive and makes it harder for non-programmers to work with the engine. Even for programmers, there is much more complexity involved in setting up scenes, factory patterns, templates, types, meta programming, and just breaking out of an OOP mindset. The architecture itself also has many quirks in its design that could be easily solved with OOP. Consider when a player reaches a portal and presses Enter to progress. Players and portals both have location and collision components, but how does the collision system know whether two specific objects are a player over a portal, and not the hundreds of other potential collisions? Specific features that involve only a few, or even just two entities like this, require their own hack components and systems. All these additional files add technical debt, even worse, since they are disconnected by design, making debugging across multiple files and systems all the more confusing. Passing information between entities and scenes also requires dumb workarounds and/or complex argument forwarding. Giving game state information to a new scene required an inheritable scene arg component, where the engine would try to load any arguments into newly created scenes, something OOP was designed for. This trade-off in complexity for shear performance and scalability is definitely worth considering, but may not be practical without a good understanding of ECS.

- Ideal memory management and performance

- Easy to scale and compose across entities

- Singular/Niche components/systems add complications

- More complicated than OOP (templates/managers/mindset, etc.)

In my opinion, the best solution is a mix of both architectures. The vast majority of game engines define their nodes/objects/building blocks as objects, which can be mixed with composition of reusable objects. Systems that work across many objects can also be incorporated into the engine, with more niche interactions handled directly between those few objects. Nevertheless, the best way to learn your preference is by trying to implement it from scratch, for which I am really thankful for this opportunity to attempt. Feel free to give both games a try, it's free after all~